Loss and Damage – the residual effects of climate change that could not be avoided or reduced through adaptation and mitigation activities – are already a lived reality for people worldwide, with around a million family members lost and over 98 million displaced and homeless. Poor and vulnerable countries and communities are the least responsible for the cause, which manifests in extreme weather events and water-related disasters1 such as cyclones, floods, and slow-onset processes such as sea-level rise.

The long-debated issue of financing Loss and Damage in the UNFCCC gained traction at COP 27 due to the inclusion of the item on the COP agenda for the first time. The inclusion of financing loss and damage as a sub-agenda under “Matters related to finance” is the icing on the cake. Those negotiating parties pursuing the inclusion of loss and damage as a third pillar in the UNFCCC, in addition to adaptation and mitigation, may not have the luxury of being delighted, sitting back, and relaxing. Concerns include the operationalising of the Santiago Network under the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) and the uproar over developing-country compensation claims for historical loss and damage.

The Santiago Network, also known as the WIM’s implementation wing, was established in Madrid at COP25 and given the responsibility by the Glasgow Climate Pact at COP26. It envisages mobilising pertinent stakeholders’ technical assistance to implement successful strategies for preventing, reducing, and addressing L&D at the local, national, and regional levels in developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change. The critical concern is why a new institutional setup, the Santiago Network, is necessary, given that the WIM already provides an institutional foundation. According to Least Developing Country delegations, the UNFCCC has historically failed to give the loss and damage issue the proper attention it requires, and Executive Committee (ExCom) in the WIM is already overburdened, finding it difficult to carry out all the activities in its work plan.

COP27 in Egypt is focusing on establishing the structure of the Santiago Network, which preferably includes the three components: an advisory body comprised of the participation from different groups, i.e. G77 and China, LDC, AOSIS etc., an organisation to host an (independent/autonomous) secretariat and a network of a broad range of organisations, and experts from all regions, providing technical assistance. The critical point of discussion in the negotiations is the advisory body’s and host organisation’s Terms of Reference, as well as the membership selection criteria. Every country party agreed on the importance of implementing the Santiago network. However, there is some debate about whether the secretariat should be an independent authority or separate from the ExCom or the UNFCCC.

After attending the initial negotiation session, I am concerned that the protracted discussion of institutional structure would cause the most crucial topic, specifically financial loss and damage, to be overlooked. The way it was overlooked in Madrid and later in Glasgow, it is much easier to debate and deliver around the institutional structure instead of agreeing on the longstanding issues of liability, compensation and finance.

After 30 years of shady distraction, this African COP, after witnessing a series of warmest years and millions of dead and homeless families in one of the world’s most vulnerable regions, is finally time to deliver on Loss and Damage. Egypt’s COP27 must work hard to establish a Loss and Damage Finance Facility to coordinate information on the need to address Loss and Damage and to provide a financing mechanism to address it. Negotiators should stop deciding who is guilty and instead focus on obtaining support for those affected from those who have the ability to do so. Support can be provided in a variety of ways, not just financially. Many other options, however, should show solidarity with those who have suffered and assist them in rebuilding resilience. In turn, those assisting may receive similar solidarity when affected, keeping in mind that climate change loss and damage is not local but rather a global catastrophe.

The COP 26 Outcome: A Retrospective for Developing Countries

After three decades of climate negotiations, the next big climate summit, COP 27, is set to open the curtain in Egypt, with the official tagline “together for implementation.” What remained in Glasgow was reviewed at the Bonn Climate Talks in June 2022. This blog primarily makes an effort to keep track of the Glasgow COP 26 outcome in order to pinpoint the agenda items on important thematic areas that deserve particular attention at the following COP.

Important Agendas of COP 26

- Climate Mitigation – Keeping the Temperature rise within 1.5 degree Celsius

- Climate Change Adaptation (Matters related to Adaptation) – Global Goal on Adaptation

- Climate Finance (Long Term Finance and New Collective quantified goal on climate finance)

- Completion of the Paris Rule book (Article 6 of the Paris Agreement)

- Loss and Damage

Progress of Negotiation

Finance: The COP Presidency issued the latest draft on November 12, 2021; however, the final text differed significantly from the draft. For example, the draft text reflects a balance between adaptation and mitigation, which was omitted in the final version. The text also includes a discussion of doubling the adaptation finance. The text further reflects developed countries’ inaction in delivering $100 billion to developing countries. The COP president’s proposal includes the phrase “notes with serious concern the gap in relation to the developed country Parties” fulfilment of the goal of mobilising jointly US$ 100 billion per year by 2020,” which is consistent with the LDC position. Climate finance measurement and tracking mechanisms are being developed as provisional (under parenthesis). At COP 27, a high-level ministerial dialogue on climate finance agreed to mobilise $100 billion. At its fourth, fifth, and sixth sessions, the Ad Hoc Work Programme agreed to establish a new collective quantified goal. US$ 351.6 million pledged to Adaptation Fund, far exceeding the COP 25 pledge of US$ 129 million. LDC Fund has received a pledge of US$ 431 million, which is significantly higher than the COP 25 pledges of US$ 184 million. The Standing Committee on Finance is asked to keep working on definitions of climate finance. Three new collective quantified goals on climate finance were established for post-2025: establish an ad hoc work programme under the CMA from 2022-2024; conduct four technical expert dialogues as part of the ad hoc work programme, and convene a high-level ministerial dialogue beginning in 2022 and ending in 2024.

Loss and Damage: Negotiation and progress on the loss and damage work programme were slower than expected. The Functions of the Santiago Network on Loss and Damage were agreed upon as one of the key achievements. A technical assistance facility for financial support for Loss and Damage has been agreed upon, and Santiago Network will be supported by the facility to provide financial support for technical assistance. However, the governance issue (reporting under both the CMA and the COP) was postponed until COP 27. (2022).

Adaptation: This year’s adaptation progress was insignificant. The agreement on a two-year work programme (2022-2023) aimed at operationalizing a Global Goal on Adaptation was the only notable progress. Aside from that, it was agreed to hold four workshops each year under the auspices of SBSTA and SBI.

Climate Change Mitigation: The key mitigation achievement was limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. The text also acknowledges reducing carbon dioxide emissions by 45 percent by 2030 compared to 2010, with a goal of reaching net-zero by mid-century. The COP decided to create a work programme to urgently increase mitigation ambition and implementation during this critical decade. CMA has requested that the secretariat update the Nationally Determined Contribution synthesis report (NDC). Beginning with the fourth CMA, the CMA has also decided to hold an annual high-level ministerial round table on pre-2030 ambition (2022).

Tangible Benefits for Developing Countries This year, the adaptation fund, which is based on voluntary contributions from developed countries, received US$ 351.6 million, while the LDC Fund received US$ 431 million in pledges from developed countries. As a result of these pledges, developing countries are expected to gain access to increased resources from both the LDC Fund and the Adaptation Fund. In the long run, once developed countries deliver US$ 100 billion, developing countries will receive an increased allocation.

Way forward for Egypt

Despite many achievements in Glasgow and Bonn, there was a general lack of progress as countries failed to reach a compromise in some critical areas, including who should pay for the damage caused by climate change and who should cut emissions further in the coming decade. A new finance mechanism for “loss and damage,” in particular, is expected to receive a strong push from developing countries after being left unresolved in Glasgow. Concerning the global goal of adaptation, the Egyptian presidency expects to use its long-aligned position with groups prioritising adaptation to transform the event into not only an “African COP,” but also an “Adaptation COP.” It is also expected that the Egyptian presidency’s vow to at least double the adaptation fund’s funding will adhere. Last but not least, the fact that the forthcoming conference is an African COP makes it the ideal location to address some of the persistent challenges facing developing countries, such as adaptation loss and damage and access to finance.

How our disaster-resilient homes will help people in coastal regions

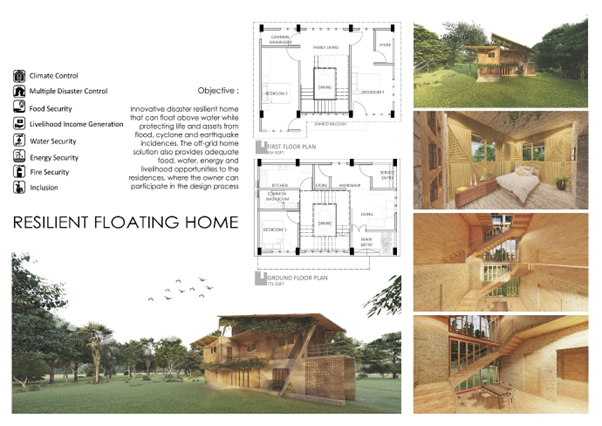

The UNESCO Centre Dundee has been probing action research on household-level integrated water management to achieve resilience through water-induced disaster management and efficient use of renewable water resources. In this research, theories of social science theories, e.g., co-design and co-development principles (see figure 1), are utilised to design a disaster-resilient home in collaboration with the ‘at-risk’ communities in the coastal region of Bangladesh. The initial floor plan, elevation and 3D rendering are shown below in figure 2.

Its main characteristics are as follows:

Hazard protection: The home has an amphibious foundation that allows it to float above flood water. It can also withstand a category four cyclonic storm and an earthquake with a magnitude of eight on the Richter scale. It grows stronger in a salty environment over time and serves as a makeshift home in the event of displacement during river/coastal erosion.

Food security: The Home produces enough food to support family members to achieve food security. The aquaponics method makes the best use of renewable water to grow fish and vegetables.

Net-Zero Transformation: On the way to achieving the Paris Agreements ‘Net Zero’ agenda, a household’s energy security is ensured through the use of various renewable energy options. In the presence of sunlight, photovoltaic cells are used, and wind turbines are used concurrently depending on the availability of air. Furthermore, biofuels are made from lavatory and kitchen waste.

Nature-Based Solution: This house has been built in accordance with the principles of the ‘Nature-Based Solution,’ using environmentally friendly, cost-effective, readily available, and locally sourced materials. Renewable sources of local materials such as bamboo and soil are extensively used based on the principle of ‘circular economy’.

Capacity Building: Training and employing locals in the construction process has resulted in technology transfer and the creation of new livelihood opportunities in the fields of ecological construction. The materials and special designs used in the construction of houses based on ancient ecology principles, e.g., Vastu principles, have ensured the best use of natural light and air.

Climate Control: Energy modelling results depict that the summer and winter indoor temperatures will naturally range between 18 and 26 degrees Celsius throughout the year. The building materials used in the house provide adaptation co-benefits from greenhouse gas sequestration, which has the potential to absorb approximately 6 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent greenhouse gas over the lifecycle. Researchers believe that after the necessary research and development, the three-bedroom house with a floor area of about 1,600 square feet could be valued just at £2,500 to £ 3,500 for ‘upscaling’ and used to address the risks of climate-vulnerable communities all over the world.

Sustainable Development: The cost of building the same size duplex home in Bangladesh is about ten times higher, and up to fifty times higher in developed countries. Furthermore, its durability is several times that of conventional building materials, and it provides health benefits because no harmful chemicals are used in its construction. Thirteen of the seventeen sustainable development goals can be addressed by various disaster-resistant house features.

The construction of Disaster Resilient Home: Resilience Solutions in Bangladesh started constructing a disaster-resilient home prototype since March 2022 under the planning and supervision of the UNESCO Centre for Water Law Policy and Science.