Post by Andrew Allan, Chris Spray, and Elaine Robinson

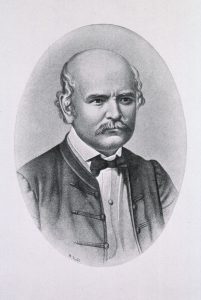

Yesterday was the 202nd anniversary of the birth of Dr Ignaz Semmelweis, the Hungarian ‘father of infection control’. It was Semmelweis who identified the need for hand washing by surgeons in order to prevent the spread of disease, presaging the later work of Pasteur and Lister on germs. The story of Semmelweis’s innovation, his ultimate failure to convince the authorities and his ignominious death is a tragic one, the reverberations of which are still of great relevance today.

Semmelweis was an obstetric surgeon in Vienna’s main hospital in the 1840s. The hospital ran two maternity units, one doctor-led and the other run by midwives. The mortality rate in the former had risen to three times that of the latter, following the decision by Semmelweis’s superior to introduce autopsies to the hospital. Surgeons in the first clinic would work on cadavers in the morning before moving to the obstetric wards, but crucially would not wash their hands in between. Although he did not fully understand the transmission process, Semmelweis reasoned that some as yet unidentified diseased matter from the autopsies might be the cause, and this could perhaps be removed by effective hand washing. If correct, then the number of women infected with puerperal fever and subsequently dying could be reduced. Despite the observed success of hand washing measures in the hospital in bringing down the number of deaths, the medical establishment refused to accept his findings. There were a number of reasons for this, not least their resistance to change but perhaps also because they could not admit that their malpractice was actually killing women. A frustrated Semmelweis was committed to the brutality of a Vienna asylum which ultimately killed him.

Many analogies and extrapolations can be made from this story in relation to modern day water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) practices and gender imbalances. Applying a liberal degree of artistic licence, there are also possible echoes in the wider area of integrated water resource management. There is an immediate topicality in relation to the benefits of hand washing in the context of COVID-19, but a wider interpretation highlights the need for evidence-based policy. Policy and its implementation need to be responsive to improvements in scientific understanding – recent reporting on the fact that many US flood maps have not been revised for years and therefore no longer accurately reflect flood risks is a case in point. The IWRM paradigm is supposed to be a self-improving system, but this fails if it does not incorporate scientific progress.

The Semmelweis experience also illustrates the need for precautionary approaches. The reason his approach worked was not understood at the time, but the authorities at the hospital rejected his theory despite its demonstrable benefits. A more precautionary response would have sought to capitalise on the advantages for maternal health and to work out the scientific detail later. Many of the reasons that prevented Semmelweis’s conclusions being put into more general practice apply to the governance of water resource management, whether through institutional inertia; knee-jerk responses to indigenous knowledge, foreign expertise and citizen science; or failure to adapt to changing climatic circumstances.