Post by Elaine Robinson and Andrew Allan

This week is World Water Week. To honour this event, today’s post will be looking at an example of the relationship between politics and water challenges, one of the issues being covered at the Stockholm event this year.

Getting the attention of political leaders can be difficult, especially if they are not directly affected by the problems. Last month, July 13th marked the 150th anniversary of the Royal opening of Victoria Embankment, part of the River Thames in London. Featured prominently on a memorial there is a representation of Joseph Bazalgette, chief engineer of London’s Metropolitan Board of Works. His ideas, of which the Victoria Embankment is an integral part, led to the sewer system that still underpins London today. This system only came into being because the politicians in Parliament were so overwhelmed by the stench of the sewage-laden Thames outside their windows.

During the 1800s, various types of waste flushed into the River Thames, resulting in diseases such as cholera as well as producing a terrible odour. Such was the state of the river that it was featured in newspapers of the time, and major figures such as Charles Dickens wrote about the “offensive smells” of the river in letters to friends. In an especially prescient letter titled Observations on the Filth of the Thames, Michael Faraday described the foul-smelling, dark sludge that the river had become, and warned: “I fear it is rapidly becoming the general condition. If we neglect this subject, we cannot expect to do so with impunity; nor ought we to be surprised if ere, many years are over, a hot season give us sad proof of the folly of our carelessness.” Faraday sent this both to The Times and the Houses of Parliament in 1855. In 1858, the resulting summer’s hot weather caused the effluence in the Thames to produce a powerful stench, dubbed The Great Stink.

The work of Dr John Snow and Rev Henry Whitehead suggested that outbreaks of cholera could be caused by a dirty water supply, but the theory held at the time was that of miasma – airborne disease caused by foul smells – and thus the idea was not paid much heed. The miasma theory may have been incorrect for outbreaks of waterborne disease such as cholera, but crucially, it led to Parliament agreeing on the construction of a new sewer system for London. The development of the London sewers was part of a mid-19th Century process to improve sanitation in cities, after a number of cholera outbreaks occurred across Europe.

Bazalgette created a new network of sewers, collecting both waste and rainwater. Pumping stations were built, and the Chelsea, Albert, and Victoria embankments were created to aid the development of the sewer system. Over 1,000 miles of underground sewers now cater to London. Bazalgette had the foresight to incorporate a degree of adaptability, to cope with an expanding population, but London’s growth has become such that new development is needed. The Thames Tideway Tunnel – London’s new “super sewer” which began construction in 2016, aims to service this need. Although Bazalgette’s sewer system helped to ensure that diseases such as cholera did not have such a hold on the citizens of London, the sewage was carried out to sea rather than treated.

One the of the remarkable things about the construction of Bazalgette’s system was the lack of action on the part of the politicians at the time: they were only willing to agree to his proposed plans when it directly affected them, rather than the thousands of other Londoners already suffering. In a fiery article on the 18th of June 1858 The Times noted this self-interest: “We can bear the calamities of our neighbours with remarkable self-possession, but when the black ox sets his hoof upon our own foot it is wonderful how filled we are with sympathy for all mankind.”

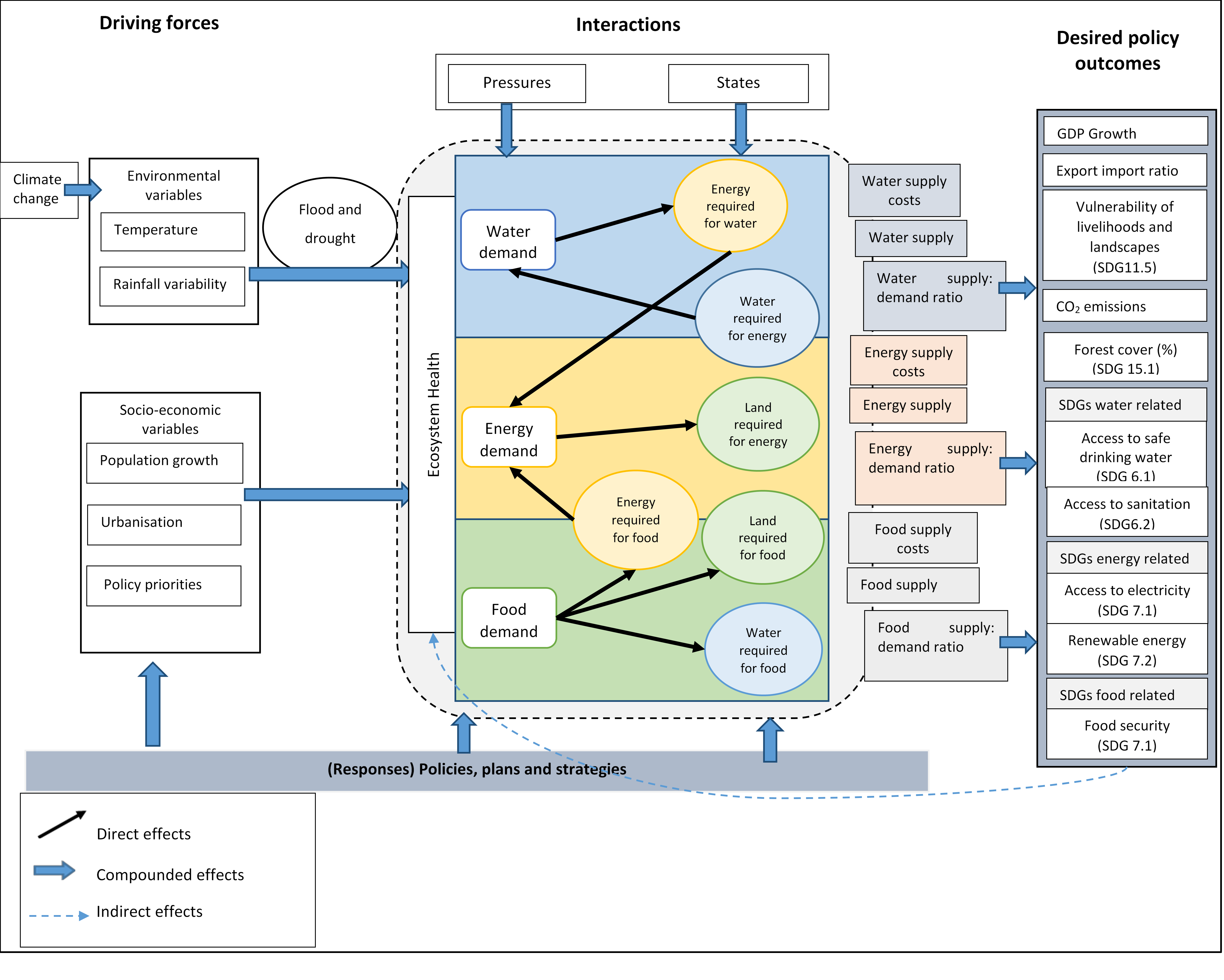

Work on ensuring access to clean water and sanitation continues at a much greater scale, most notably in the context of SDG Targets 6.2 and 6.3, which focus on sanitation and hygiene, and water quality and wastewater. 2.4 billion people still lack access to basic sanitation services. Diarrhoeal diseases resulting from water-borne contaminants infect millions every year and are one of the most severe threats to childhood health. Ensuring that politicians understand the need for action not only in their own countries but globally is crucial – the fact that Water and Politics is one of the key themes in Stockholm this week highlights how much work still has to be done.