Post by Cathy Smith

The latter twentieth century saw a global shift towards ‘participatory’ approaches in environmental management. Calls for public participation have had different emphases, from normative arguments that foreground democracy, equity and human rights, to pragmatic arguments that direct involvement makes people more likely to agree with management interventions, or that local knowledge helps adapt management to context. Since the late 1990s the public right to participation in environmental management has been enshrined in various policies and legal instruments with relevance for Scotland’s fresh and coastal waters.

In 1998, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Aarhus Convention established the rights of the public to participate in environmental decision-making. In 2000, the European Union (EU) Water Framework Directive called on member states to consult the public and involve stakeholders in creating river basin management plans. In 2008 the EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive similarly called for public participation in creating national and regional marine plans. Scotland has ratified these directives, creating plans for two River Basin Districts and starting marine planning processes with a National Marine Plan and regional plans for the Clyde and Shetland Isles. Scotland has also adopted the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, of which Target 6.B, under Goal 6 (sustainable management of water and sanitation for all), calls for the ‘participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management’. There are also a number of local stakeholder partnerships that have created plans for integrated river catchment or coastal management independently of Government-led processes, including the Tweed Forum.

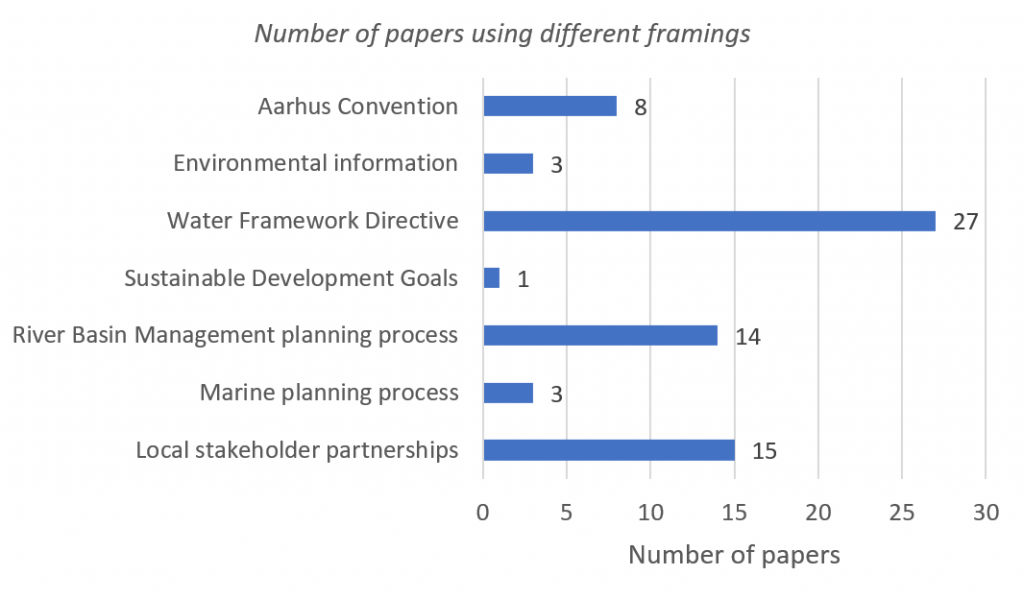

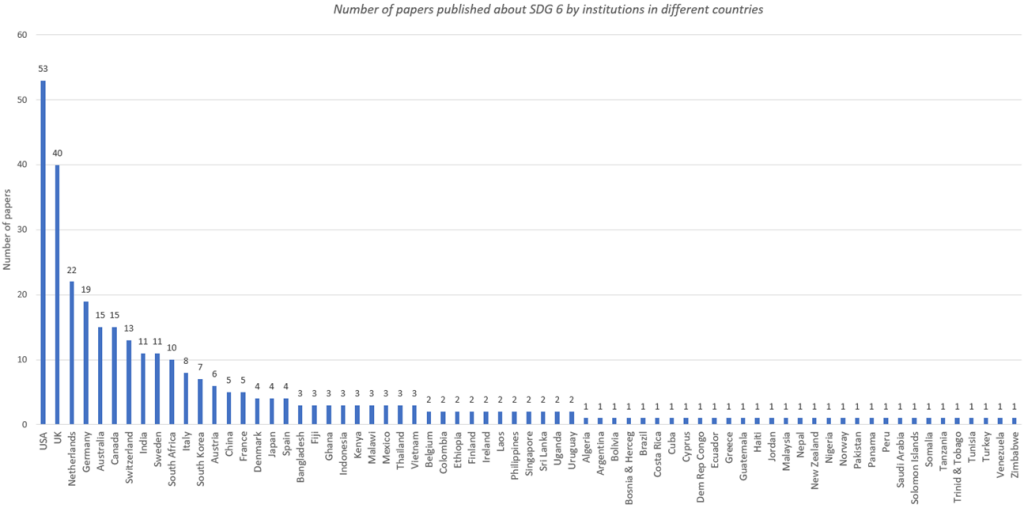

We recently used Clarivate Analytics’ Web of Science (WoS) to examine which of these policy and legal instruments are referenced in academic papers that discuss public participation in fresh or coastal water management in Scotland. Our search threw up 46 papers, all published since 2000. The Water Framework Directive is mentioned in 59 percent of the papers. Equal amounts of papers referenced the government-led river basin management planning and marine planning processes as referenced independent local stakeholder partnerships. Interestingly, the Water Framework Directive was used to frame both government-led and independent planning processes. The SDGs are mentioned only in one of the papers (and this paper does not reference any of the goals specifically). This fits with a finding we shared in a recent blog post, that little research around SDG 6 is centred on developed countries. Far more could be done to link ongoing efforts in Scotland to the SDG agenda.