What I am Reading Now…

Rosalind Nashashibi

May 2024

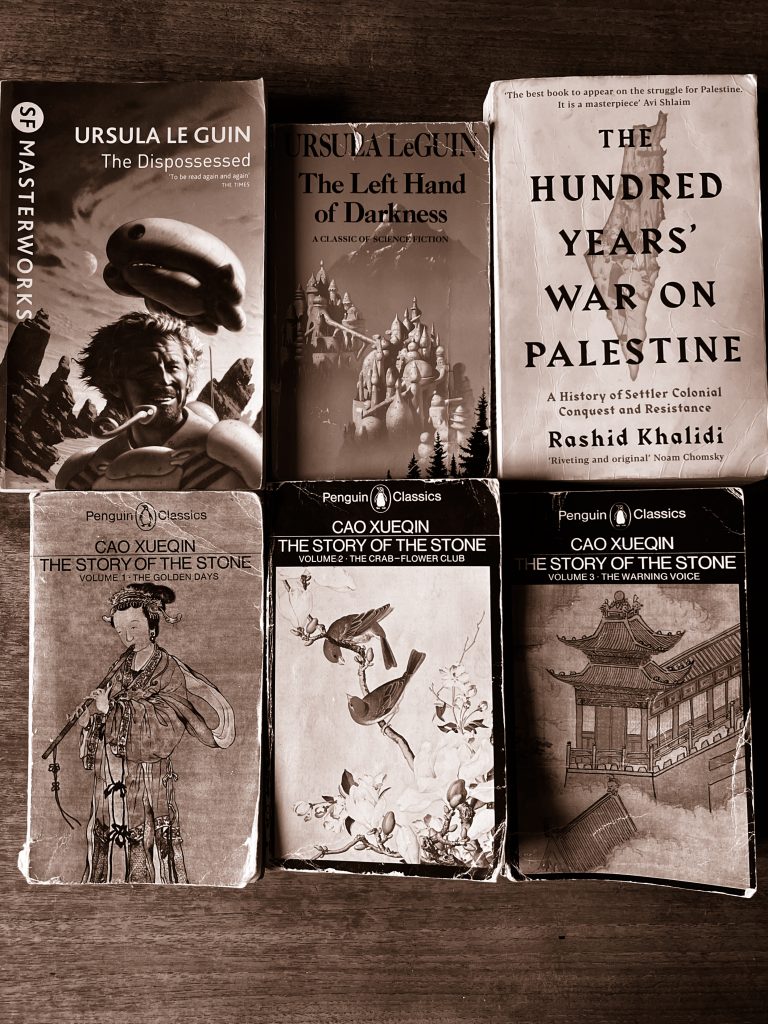

Last summer my friend Gintaras bought The Story of the Stone by Cao Xueqin in a second-hand bookstore for my daughter who was fifteen at the time. Unsurprisingly this 18th century novel was a bit too slow and pedantic for her age. Later I picked it up and have been engrossed for some weeks now in the intricacies of the social and administrative life of a large noble family with their huge number of servants.

The Story of the Stone is like Proust without Proust; without the egomaniacal ‘I’, we get to pour in and out of the thoughts and idle conversations of women, children and men at all levels of the household, with particular insight into the private worlds of the women and girls. Flowers, clothing and food are described in great detail, as are stipends, equipment and organising principles of the household. None of that explains the books’ fascination. The relationships are tantalisingly unclear, the young people that live in the pavilions in the garden have poetry writings contests and their drinking games involve reciting lines of poems and prose, they are modest in ways we are not, and unabashed about things we would never reveal. Cao Xueqin understands the immersive hierarchy and power structures in nuanced ways. At the heart of the novel is a kind of wonder at the beauty and brutality of this corner of imperial China. Cao Xueqin had a talent for seeing his world with a sharp and loving eye, and then unravelling it in front of the reader like a beautiful carpet.

The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine by Rashid Khalidi is by far the most moving and helpful book on Palestine I have read. Rashid Khalidi recounts the relentless destruction of Palestinian hopes via the capitals of the West and the Arab world, the machinations of Britain, USA, Lebanon, France, Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Russia and of course Israel and Palestine are all laid out in clear and beautiful prose, with many personal recollections and anecdotes, as Khalidi and his father were at the periphery of many of the diplomatic events. I could say, if you want to understand the twentieth Century and colonialism, read this, or if you want to know the history of Palestine from the First World War till today, get this book, but that’s not the only reason, it’s genuinely a really good read. If you’ve been alive longer than fifteen years you are sure to remember many of the events that are described here with insider insight, and you will say to yourself ah, yes, that makes sense. It’s not complicated after all. It’s the reality of life under a settler, colonial, apartheid power.

I’ve been reading Ursula K. Le Guin since I was a teenager. The Wizard of Earthsea trilogy was my first adventure with her and I returned to it many times. In my thirties I found out she also wrote for adults and read her novella Buffalo Gals, about a girl who survives a plane crash into the Southwestern U.S desert, takes up with the animal community there and lives a while with the coyote; a trickster, wise woman who talks to her own shit, is promiscuous and fiercely cares for her. Later I got into her novels such as Left Hand of Darkness, Coming Home, and The Dispossessed. Unfortunately, there is not much left to read now but her wisdom and style are still a big influence on me. I recently made a feature film inspired by her short story The Shobies’ Story. She was a true radical, she took apart power and gender and capitalism and the family and society, she held it all with love and with fierce curiosity, and she wrote new stories about her alternative structures for living. That is why she was known as a Sci-Fi writer, because she dared to suggest alternate realities to our own.

The protagonists in the 2024 film No Other Land are Basel Adra and Yuval Abraham, both activists, journalists and filmmakers. After the film won the Panorama Audience Award for Best Documentary Film and Berlinale Documentary Film Award at the Berlin international Film Festival, Adra and Abraham spoke movingly about the inequalities in Israel Palestine and were immediately slammed by Germans as antisemites, despite Abraham being an Israeli Jew. This was all I knew about the film until I saw it just recently. I’m not surprised it has frightened those who would have us believe that Israel is a democracy and a rational and benign state. It’s a devastating portrait of a group of Palestinian villages on Palestinian land in the mountains of the West Bank; who have been fighting for decades just to stay on that land. Israel has designated their villages as a military training ground. The villagers of Masafer Yatta who have not already fled, can live for only one purpose, to protect their homes and schools from destruction and rebuild them during the night after a demolition. In between these traumatic and extremely violent events, they are attacked by armed illegal settlers, protected by the same IDF soldiers. We follow Basel, who’s activist family are at the heart of his community, with his new friend Yuval who comes from across enemy lines to support and document their struggle. The most beautiful parts of the film are the slow build-up of trust between the protagonists and our increasing familiarity with the villagers in their hardships and small joys. In one absurd piece of archive footage we see the villagers, including Basel’s father, alongside Tony Blair when he visited the village in the nineties, temporarily saving the buildings on one street, merely by having walked along it.

Faya Dayi (2021) is one of the most sensual films I’ve ever seen, and yet it’s also in touch with reality in a profound way. Beshir documented, and I guess workshopped, this film with a community who farm Khat, the herb at the centre of their lives. Khat is threefold, as extremely lucrative cash crop, as a spiritual tool within Sufi mysticism and euphoric escape, and also their ball and chain, due to the hard and extremely monotonous work of growing and harvesting the stuff. There is literally nothing else, no other work. The young people dream of escape, some of them pull back from the brink but others set off to meet people smugglers on what must be extremely hazardous and lonely journeys. The film itself seems to be intoxicated and intoxicating, with the sounds, movement, light and shadow sending the viewer into a kind of trance. What I love about it, is how you can be with Beshir in the trance she creates, and yet fully aware of the human reality she brings to us.

British Palestinian artist Rosalind Nashashibi is a painter and filmmaker. In both media she is preoccupied with looking, to the extent of passing over onto the side of the subject in a way that can be disconcerting and yet deeply empathetic. Based in London, Nashashibi received her BA in Painting from Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield (UK) after which she attended the Glasgow School of Art, Glasgow (UK) where she received her MFA. In 2020, Nashashibi became artist in residence at the National Gallery in London (UK). She was a Turner Prize nominee in 2017, and represented Scotland in the 52nd Venice Biennale. Her work has been included in Documenta14, Manifesta 7, the Nordic Triennial, and Sharjah 10. She was the first woman to win the Beck’s Futures prize in 2003.

Reading

Volume 1, The Golden Days

Volume 3, The Warning Voice

The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, Rashid Khalidi (Profile Books, 2020)

All by Ursula K. Le Guin

No Other Land (2024), Dir by Basel Adra, Hamdan Ballal, Yuval Abraham and Rachel Szor

Please note the views published in What I am Reading Now… are personal reflections of the contributors.

These may not necessarily represent the views of the University of Dundee.

Readers who wish to make a donation to support Medical Aid for Palestinians can do so here.

———