What I am Reading Now…

Omar Kholeif

October 2025

Draft Curriculum for an Errant Body

The act of transit has become synonymous with a venture of boxing. Of compartmentalising parcels of errant history[1], fragments of the African diaspora and its adjacencies. Movement has precipitously become endemic to my life since birth. Each undertaking now involving recurrent acts of immense physical labour, which seem almost ritualistic. The wrapping of glazed pictures with polythene and the subsequent doubling up with bubble wrap. The examination of archival boxes of newspaper clippings and hand scrolled notes. The encounter with notebooks used to annotate books that I have come to read and re-read over time—the source code.

The act of constituting time and space for this activity is where the discipline for all things curatorial begins for me. Melancholy has a way of wrapping itself around me in such moments, becoming a chokehold. Revisiting the lost, the dead, and the dispossessed in each act of consolidation can become a grip one must tender with.

In Sharjah, I pack-up my books into tote bags in the former seafarer’s home that has been beautifully transformed into a space for art. It is 46 degrees Celsius out. I prop open the large brown wooden doors, revealing a vista to the sea. I venture back in time, to Edward W. Said’s Out of Place: A Memoir. There are innumerable moments in these pages, where I feel life so intimately expressed that I wish I could cleave the words to my person. Language is not only power and weapon, but also our bridge. In Out of Place, a bell-chimes, the echo never ceases to reverberate:

My first obligation has not been to be nice but to be true.

There was always something wrong with how I was invented.

I have retained this unsettled sense of many identities—mostly in conflict with each other—all of my life.[2]

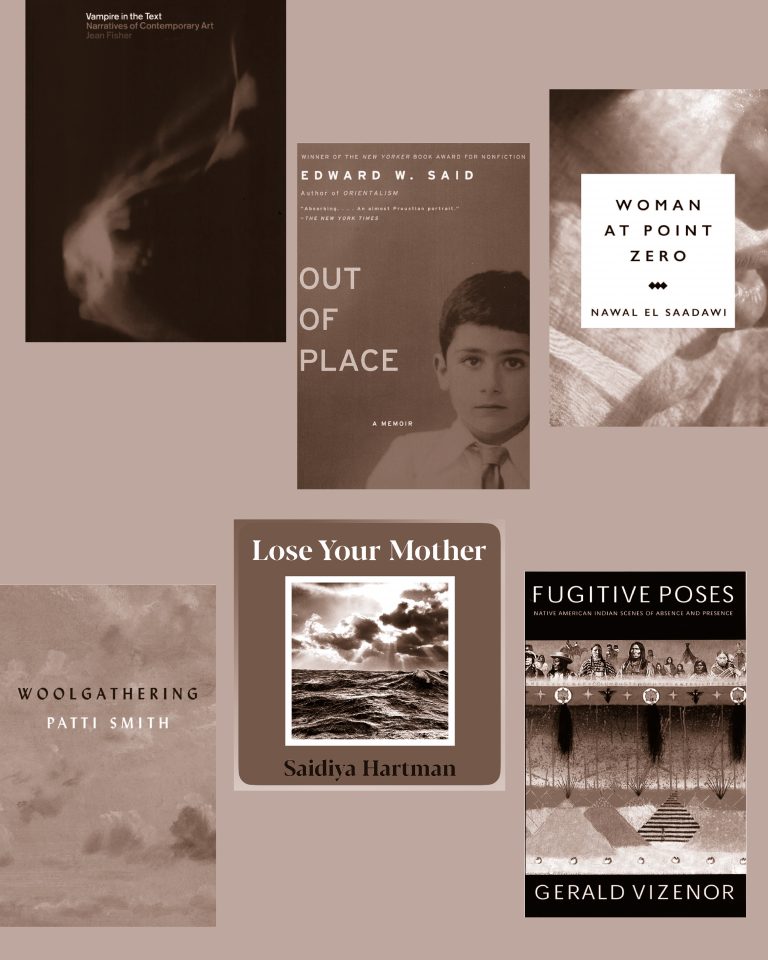

Pithy as I have made these sentences read, they could be applied to various forms of exile and self-exile. Assembling an archive, particularly one that is anchored around ‘the interstitial’ I have come to understand is a disciplinary practice. I was taught this by my late mentor, Prof. Jean Fisher, whose ‘Tricksters, Troubadours – and Bartleby: On Art from a State of Emergency’. I re-read. Here, Fisher explicates the difference between aesthetic politics and social activism in the global arena. Her musings feel apt in an era of all-encompassing emergencies. For Fisher, there is a suggestion that art could become a mode of resistance. I wish that Jean had lived long enough for us to debate Saidiya Hartman whose ekphrastic experience materialising her concept of “critical fabulation” has enabled me with a seat of agency. For it offered me the tools to narrativize stories of those disinherited from history. Her memoir, Lose Your Mother first published in 2006 has served as a bible. I re-read it whenever shorn. The audiobook keeps me company on planes and trains.

I was born in Cairo to Egyptian and Sudanese parents. I never saw a ‘Sudan’ and have lived most of my life in what I now refer to as a ‘reclaimed diaspora’. Yet, my research has consistently engaged the African continent and its diasporas. All the same, the glass pane of duplicity, of being multiply othered and exiled rings and stings in such manifold form. This sense is articulated with a razor’s edge by Hartman, as she seeks to situate herself in Ghana:

To lose your mother is to be severed from your kin, to forget your past, [and to inhabit the world as an outsider]…losing a “forever lifeline” and a deep, unique attachment.[3]

Her book is a story of the afterlives of slavery and the ghosts that haunt us. It acknowledges the burden of endurance required in embodying the act of ‘living with the dead.’ The form of the travelogue creates a structure for the pursuit of ancestral knowledge and suggests a methodology of how one might assemble a toolkit to recount a time that has been lost to us.

I begin to assemble my own toolkit. Where are the aunties and sisters? Perched on a stoop along the corniche in the UAE, Naomi Beckwith, a friend, and the embodiment of a perfect sister, cuts through my attempted professional art-speak, and suggests that we take pause. Within minutes, our conversation freewheels from coffee to death, abstraction and the longing for a family that some of us shall never have. Summoning ‘radical presence’, Beckwith points me to the work of Anishinaabe scholar and poet, Gerald Vizenor and his book, Fugitive Poses (2000).

She emphasizes his popularisation of the portmanteau ‘survivance.’ Perhaps this literary journey might suture the open wound of leaving a place [Sharjah] where I have lived longer than almost anywhere—the place closest to my supposed ‘ancestral’ route and roots.

I probe how society defines one’s notion of living in a place—is it to occupy, inhabit or is it to endure, insist, or resist, leaving? For memory insists that we live in many places at once: history is a palimpsest overlaid onto a cityscape much like modular architecture.

I have carried Vizenor’s books with me almost daily since Beckwith’s visit. Sketching the coordinates for a curriculum for my own dreaming. Accompanying it are a series of familiar friends, several editions of Patti Smith’s first memoir, Woolgathering first published in 1992, where Smith realises that ‘to rescue a fleeting thought’ could become a vocation unto itself. Etel Adnan’s In the Heart of the Heart of Another Country (2004), James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son (1955) and Nawal El Saadawi’s Woman at Point Zero (1975) are also by my side. Sketched in the margins of these pages, in moments between wakefulness and sleep, in the undulating shape of a dream is where I constitute a semblance of home.

—

[1] I pay reference to curator Naomi Beckwith’s AICA Distinguished Critic Lecture delivered in partnership with the Vera List Center at The New School, New York, ‘Curating the Errant Form.’ Accessible here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nyyYjtWXS6k. Accessed 10 September 2025.

[2] Edward W. Said, ‘On Writing a Memoir’. The London Review of Books: Vol. 21 No. 9 · 29 April 1999. Available at: a https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v21/n09/edward-said/on-writing-a-memoir, accessed 10 September 2025.

[3] Saidiya Hartman (2006/7) Lose Your Mother: A journey along the Atlantic slave route. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Dr Omar Kholeif is an author, curator, historian, and artist. They are Professor of Global Art Theory and Practice at Glasgow School of Art and Programme Leader of the Master of Letters in Curatorial Practice (Contemporary Art) with University of Glasgow. In 2012, they founded artPost21, a platform for artists and their “dreamwork”. They are series editor of imagine/otherwise published by Sternberg Press, and the author of Huguette Caland. Until recently, they served as director of collections and senior curator Sharjah Art Foundation, UAE; Manilow senior curator and director of global initiatives at MCA Chicago; curator at Whitechapel Gallery, London; co-director of programmes at SPACE, London; senior curator at Cornerhouse, Manchester, among other roles. They are visiting professor at MIMA Research Unit, Teesside University, UK.

Reading

In the Heart of the Heart of Another Country, Etel Adnan (City Lights Publishers, 2004)

Please note the views published in What I am Reading Now… are personal reflections of the contributors.

These may not necessarily represent the views of the University of Dundee.

Readers who wish to make a donation to support Medical Aid for Palestinians can do so here.

———

Previous Issue: Amal Khalaf, September 2025

Next Issue: Titilayo Farukuoye, November 2025