What I am Reading Now…

Mona Benyamin

April 2024

I

We, Palestinians, are born into a world that announces us dead before we even take our first breath. Therefore, the only logical thing for us to do in the eyes of such a world—is die. To depart silently, interrupting no one. We live in this world not as human beings but as ghosts who accidentally made their way into the realm of the living, and so, anything we do that draws attention to our existence is deemed a violent disruption. It is not terror we inflict upon this world but horror. Terror is the feeling of dread that precedes the horrifying experience, but how can anyone anticipate us if we don’t exist? Horror, on the other hand, usually follows the frightening sight, and what could be scarier than hearing the corpse you stumbled against suddenly scream in pain?

The only way for us to live is by haunting you, the living.

***

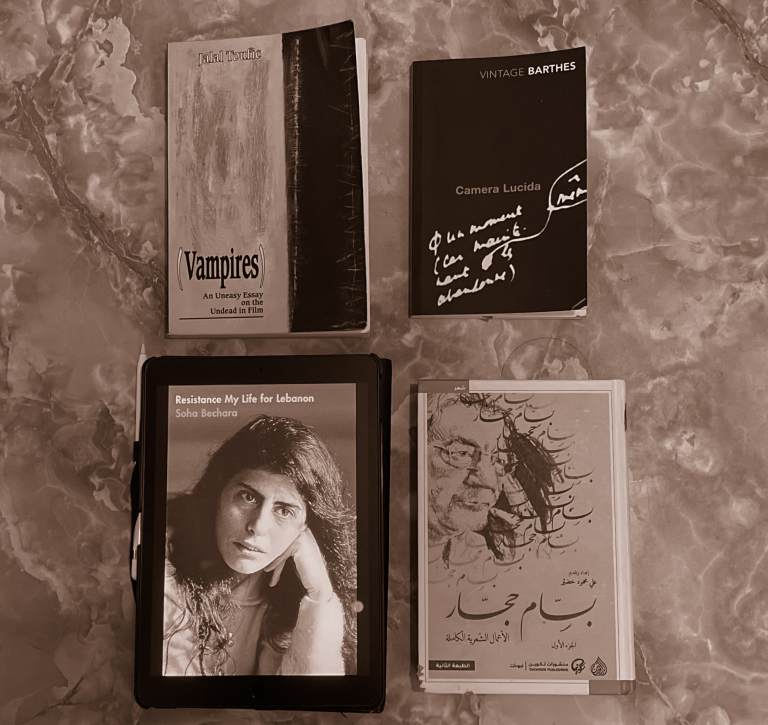

The first book I open is Jalal Toufic’s (Vampires): An Uneasy Essay on the Undead in Film; it tells me that ‘The ghost does not have a memory; he is rather the spectral embodiment of a memory, that of his unjust, untimely death and the consequent need to redress it and settle some unfinished business: he is really like an audiovisual record that each time plays back the same message.’

I think of this little girl from Gaza, who is maybe 8 or 9 years old; she assertively declares to the camera recording her:

“I will remain steadfast on my land, until the last blood drop in my soul, until my very last breath […] The children of Palestine do not abandon her [the land]”.

I also think of the words of the late Palestinian poet Tawfiq Zayyad: ‘Here, we shall remain / A wall on your chests. / We starve, / go naked, / sing songs / and fill the streets / with demonstrations / and the jails with pride. / We breed rebellions / one after another. / Like twenty impossibles we remain / in Lydda, Ramlah, and Galilee’. and how they linger in the shadow of that little girl’s voice.

II

‘For Death must be somewhere in a society […] perhaps in this image which produces Death while trying to preserve life.’ Writes Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida.

Doctors at the Al-Ahli hospital in Gaza hold a press conference amidst the bodies of some of the hundreds of victims of Israel’s bombing on October 17; 19-year-old Shehab Omar Abu al-Hanud embraces his mother Ghada’s wrapped body on a hospital bed in Rafah on February 19; a bag of flour covered in blood on February 29; limbs scattered in the streets. Every day we see an image from Gaza that could end all images.

III

In 1988, at the age of twenty, Souha Béchara attempted to assassinate Antoine Lahad, the head of the militia that administered the Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon in the 1980s and 1990s. After the attempted assassination, Béchara was locked up in the notorious Khiam prison, where she was subjected to 12 years of torture and solitary confinement. In her memoir, Resistance: My Life for Lebanon, she recalls being asked by one of the men present at the scene, “Why did you do it? Why did you kill him?” to which she responded, “He’s the one killing us.”

IV

Two years ago, I lent my mom the first volume of Bassam Hajjar’s Complete Poetical Works; when she gave it back to me, I found that she’d used a pencil to underline her favorite verses and lines. When I’m lonely, I read the book again in search of my mother:*

What shall we do with so much loss / and very little heart? (I continue reading) The more I love you/the more you die/ maybe (she does not underline the following line). and I was afraid. Where do all the faces we love go? Will they return? (The world is no longer the same once you discover your mother has fears.)

* Unfortunately, Bassam Hajjar’s work was never translated into English; the lines presented here are my own translation.

V

A Hen by Clarice Lispector; my own words are not needed here.

VI

But if you must read anything today—let it be the news.

Mona Benyamin is a visual artist, filmmaker, and writer based in Palestine. In her works, she explores intergenerational outlooks on hope, trauma, and questions of identity, using humor and irony as political tools of resistance and reflection; through appropriating formats from mass media and popular media and tampering with their apparatuses, she raises questions about the value of authenticity and the tension between truth and fiction. Her films have been screened internationally in venues, festivals, and platforms which include—among others—MoMA, REDCAT, CUNY, Sheffield DocFest, and Columbia University.

Reading

Please note the views published in What I am Reading Now… are personal reflections of the contributors.

These may not necessarily represent the views of the University of Dundee.

Readers who wish to make a donation to support Medical Aid for Palestinians can do so here.

———