What I am Reading Now…

Jade Montserrat

April 2021

The five books I call on here are relatively new to me — I’ve read them in the last decade.

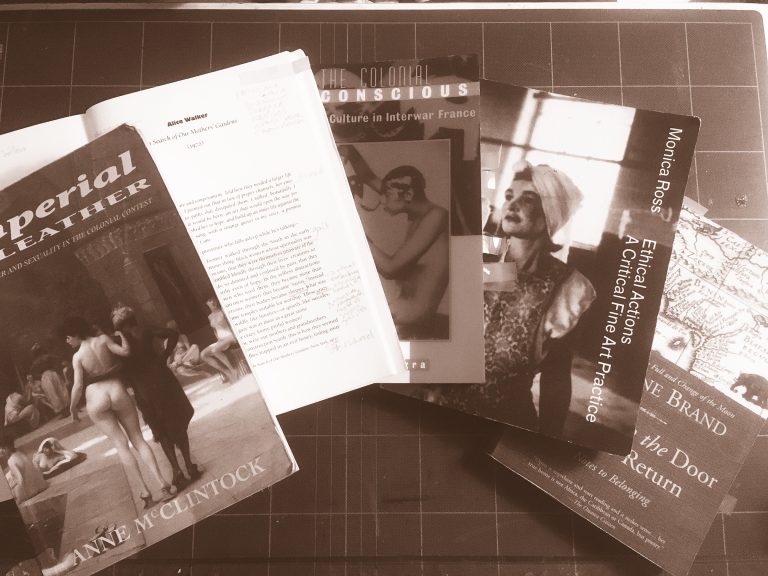

In 2011 Monica Ross performed Anniversary: An Act of Memory at Scarborough library. Ross was programmed by Crescent Arts, where I was to take a studio for two and a half years from the end of that year. Ross’s presence and performance had a profound effect on me and has influenced everything I’ve worked on since. Ross’ praxis guides anyone lucky to receive her work towards ethical actioning. Monica Ross Ethical Actions: A Critical Fine Art Practice documents works from 1970-2013, and includes essays by Esther Leslie, Eric Levi Jacobson, Alexandra M. Kokoli, Denise Robinson, Yve Lomax, and photographic documentation by Bernard G. Mills.

It was at Crescent Arts that my racial differences and feminist inquiry were bought acutely to the fore in the context of how I might make work, with a consideration of the conditions I was working under. The organisation at that time could not hold these conversations although my studio space allowed for intense periods for reflection and study which were immensely helpful. A friend of the director, a painter, was invited to exhibit at Crescent and I had the opportunity to work on installing her show, when she introduced me to McClintock’s Imperial Leather — an eye-opening read underlining how residual colonial violence glares at us from every angle in the domestic, commodified sphere. McClintock stresses, for example, how “gendering imperialism took very different forms in different parts of the world”, leading the reader to recognise — all too clearly — that a white supremacist neo-colonial agenda continues to reinforce divisions. An agenda which, in opposition to appeals for intersectional thinking, seeks to control the lives of the ‘Other’ whose race, religion, culture, gender, sex is different from their own.

I met my current PhD supervisor Professor Alan Rice at Rivington Place in 2014. I was invigilating at Autograph ABP for the exhibition Black Chronicles II on the day that Rivington Place held their memorial gathering for Professor Stuart Hall. It was a fortuitous meeting. Alan was working towards a conference focusing on Black presence and Black history in the North of England. I explained my position as a Black artist who had grown up and lived most of my life in rural North Yorkshire, and soon found myself on a panel at that conference and somewhat under the mentorship of Alan Rice. He introduced me to Dionne Brand’s A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging. I love Brand’s writing, and find that like Jamaica Kincaid’s work, their poetry is both edifying and embracing. In A Map to the Door of No Return Brand speaks first-hand of witnessing and feeling mutually her grandfather’s disappointment, in rupturing moments that I too empathise with: “We were not from the place where we lived and we could not remember where we were from or who we were. My grandfather could not summon up a vision of landscape or a people which would add up to a name. And it was profoundly disturbing.” Thinking about this quotation, I wonder at my determination not to be pushed out of the rural north of England, despite the pervasive racism and misogyny I have experienced here — I am wedded to this rural landscape by the sheer fact of its being my most reliable relation and more forthcoming with histories that I might claim also for my own. I too have no lineage to refer to, nor to honour.

I coveted Elizabeth Ezra’s The Colonial Unconscious before I had the means to purchase the book. Somehow, however, I ended up with multiple copies, which I have since made interesting gifts of. Colonial Unconscious considers the protagonist who currently takes centre stage in my thinking, Josephine Baker, by approaching her jazz-age backdrop critically, and with specific focus on French colonialism and its legacy in contemporary culture. My initial research on Josephine Baker — “Black Venus”, and as Ezra posits, the “uncivilized object of civilized cultural consumption” — included an enquiry into the balance between how she enabled control of her body and persona, representations and possible manipulations of her body, and an unapologetic quest to explore her ideas of equality and freedom. Finding herself “at the crossroads of competing cultural imperialisms” (Ezra), Baker quickly recognised that her performances were racialised as a particular type of erotic Blackness by French audiences. My project, Rainbow Tribe, takes Josephine Baker as a point of departure, aiming to signal its potential for enriching the personal and political, as an act of self-reflexivity and to recognise the spatialisation of social and political practice. The project attempts to communicate a ‘centering’ through practice, which has a precariousness to it — the reality of my personal experience. In consideration of the work I make, Baker’s body in the context of cosmopolitan Paris in the 1920s asks not to be defined by identities but by the body’s relation to everything possible.

Finally, Alice Walker’s In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens took a while for me to surrender to — I sense I was initially resistant to the text’s depths and hauntings, and in denial about my personal links to “these grandmothers and mothers of ours” – assuming that those of us, daughters of enslaved peoples, have the spiritual acumen to own those histories, despite the erasures and unknowing. The text now provides a basis for work and workshops that I continue to develop: “To be an artist and a black woman, even today, lowers our status in many respects, rather than raises it: and yet, artists we will be”. I believe that there is great strength in collaborative working. I consider research to be an indispensable method for capturing and engaging my imagination and capacity to dream new visions for my work, and more widely, to think about the future I would like to be part of creating — the world I would like to see. I think of gardening as a collaboration too, a collaboration with the earth, a friendship, a conversation, touching and being touched by the soils that provide the nutrition required for survival. Walker’s poetry is tied to ways of connecting and protesting conditions of working and living, that resound today. It evokes ravished bodies: “For these grandmothers and mothers of ours, we are not saints but artists driven to a numb and bleeding madness by the strings of creativity in them, for which there is no release”.

Jade Montserrat is the recipient of the Stuart Hall Foundation Scholarship which supports her PhD (via MPhil) at IBAR, UCLan, and the development of her work from her Black diasporic perspective in the North of England. She works through performance, drawing, painting, film, installation, sculpture, print and text, dancing her way through history and her story. Marking the archive and letting it mark her, she finds a voice within a chorus of opinions and reflecting projections of now and then. Montserrat’s work is a fracture in the linear narrative of consumption and a rigorous critique of the way cultural production scars bodies and constructs histories.

Reading

Imperial Leather, Anne McClintock,(Abingdon: Routledge, 1995)

Monica Ross Ethical Actions: A Critical Fine Art Practice, Suzanne Triester and Susan Hiller (2016)

A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging, Dionne Brand (Vintage Canada, 2001)

The Colonial Unconscious, Elizabeth Ezra (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000)

In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens, Alice Walker (1972)

Please note the views published in What I am Reading Now… are personal reflections of the contributors.

These may not necessarily represent the views of the University of Dundee.

———

Previous Issue: Minna Salami, March 2021

Next Issue: Sin Wai Kin, May 2021