What I am Reading Now…

Amia Srinivasan

November 2020

Renewed media attention on the Black Lives Matter movement, and BLM-inspired uprisings around the world, has taken many on the socialist-Marxist left by surprise. Especially in the US, one sees leftists — especially, but not only, white male leftists — decrying BLM as a bourgeois, ‘identitarian’ movement, one that only seeks (as the most prominent advocate of this view, the political scientist Adolph Reed, puts it) racially ‘proportional inequality’ rather than genuine equality for all. While I think this view is misguided, it provides an occasion for articulating, once again, the complex interdependencies between contemporary race and class formations, and explaining the importance of ‘identitarian’ movements — anti-racism, feminism, LGBT rights — to the emergence of a broad and popular working class movement.

In particular, it is important to understand why calls to ‘defund the police’ and ‘abolish prisons’ are working class demands: the anti-carceral tradition begins from the recognition not only that state violence is exercised prejudicially against black and brown people, but moreover, as Angela Davis wrote in 1971 that ‘the necessity to resort to such repression is reflective of profound social crisis, of systemic disintegration’. That crisis is a crisis of advanced racial capitalism. Abolitionism asks: what if this social crisis were addressed directly, through non-violent means? The answer, as the sociologists John Clegg and Adaner Usmani have put it recently, is that ‘waging an all-out war on the root causes of crime is equivalent to the task of building a large, redistributive welfare state that takes from the rich to give to the poor’. At the same time – as David Roediger traces in his now-classic The Wages of Whiteness – race has had a large role to play in the failure of a broad working class movement to emerge in the US. In a letter to Angela Davis in jail in 1970, James Baldwin lamented that ‘only a handful of the million of people in this vast place are aware that the fate intended for you…is a fate which is about to engulf them, too. White lives, for the forces which rule in this country, are no more sacred than Black ones…the American delusion is not only that their brothers all are white but that the whites are all their brothers.’

The question should thus not be: can the anti-racist movement ever be sufficiently anti-capitalist? But: can a working class movement afford not to be anti-racist?

Amia Srinivasan is the Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at All Souls College, Oxford. She works on feminist theory, epistemology and political philosophy. Her writing – on sex, animals, death, the university, technology, anger, politics and other topics – has been published in The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, Harper’s, The Nation and The London Review of Books, where she is a contributing editor. Her book of feminist theory, The Right to Sex, will be published in 2021 with FSG.

Reading

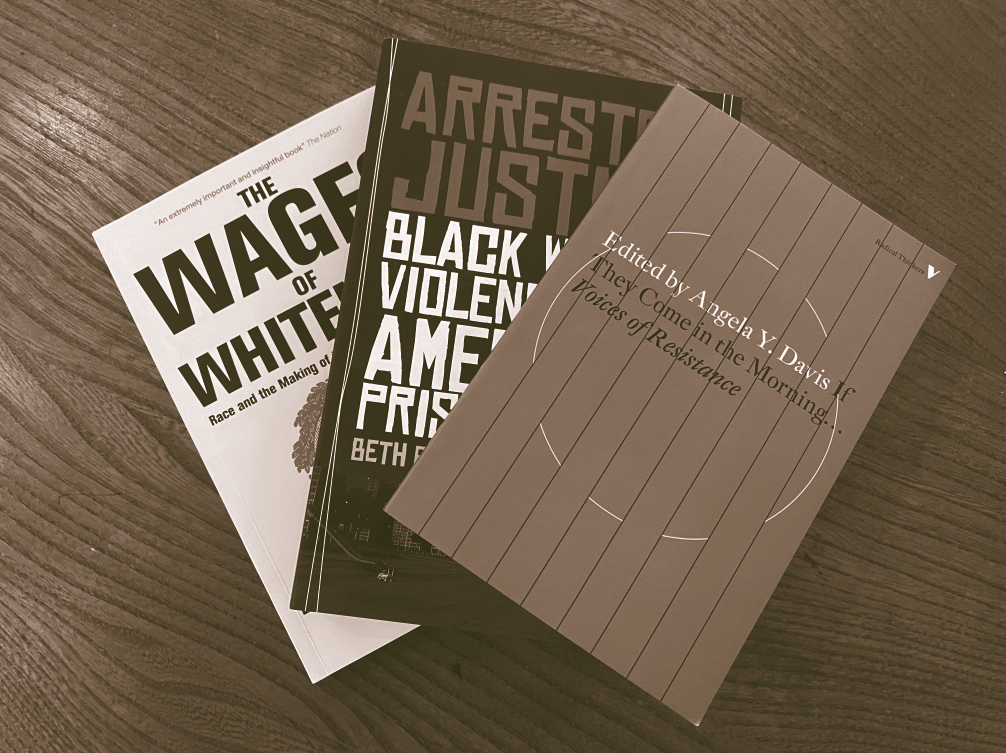

If They Come in the Morning…Voices of Resistance, Angela Davis (The Third Press, 1971)

The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class, David Roediger (Verso, 1991)

Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California, Ruth Gilmore (University of California Press, 2007)

Arrested Justice: Black Women, Violence, and America’s Prison Nation, Beth E. Richie (NYU Press, 2012)

The Economic Origins of Mass Incarceration, John Clegg and Adaner Usmani (Catalyst vol 3 issue 3, 2019)

Please note the views published in What I am Reading Now… are personal reflections of the contributors.

These may not necessarily represent the views of the University of Dundee.

———

Previous Issue: Nazia Khan, October 2020

Next Issue: Barby Asante, December 2020