What I am Reading Now…

Alia Syed

January 2026

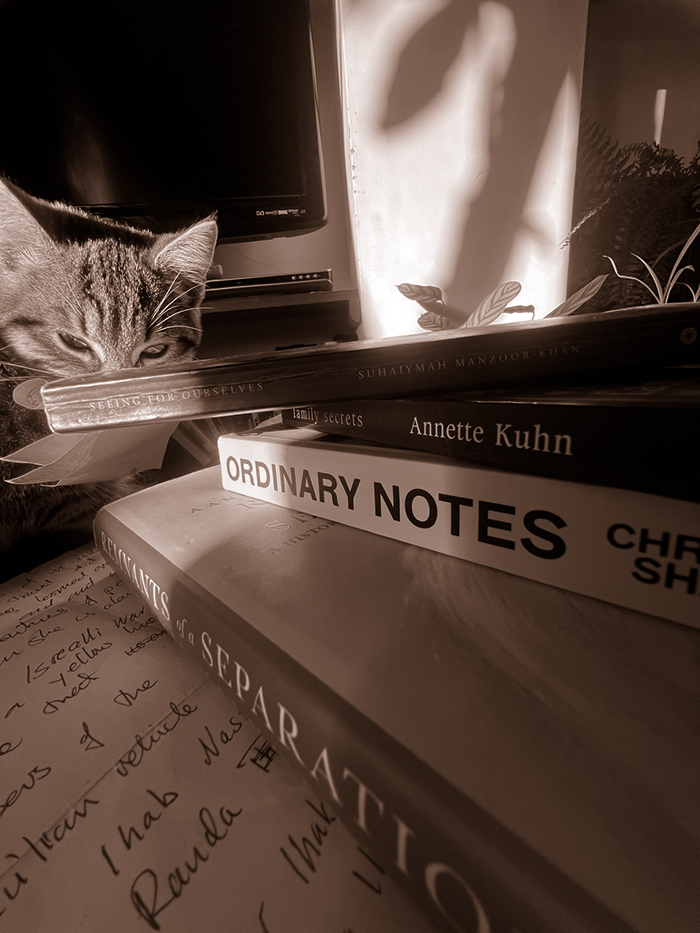

Whilst making The Ring in the Fish I read books relating to material memory, including Annette Kuhn’s Family Secrets and Remnants of Partition by Aanchal Malhotra; I needed to enter a space where I was open to other peoples’ testimonies: these works charted a self-reflexive terrain; enabling me to articulate my own concerns more clearly, unpicking interrelations between official scripts and internal remembrance. In Seeing for Ourselves Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan’s heartfelt grappling with ethical conundrums of representation was indispensable. But I’ve chosen to start with Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe a book I read after my exhibition was prematurely closed due to CCA management’s inability to adequately respond to the surge of feeling surrounding the genocide in Gaza and signing PACBI (The Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel). I found her attention to form exciting and the depth of feeling in a time of both political and personal turmoil instructive.

Last night I went back to the beginning. It was as if the pages of the book were falling, transmuted into concrete evidence that I no longer wanted to sift through.

Note 2 Verb: to notice or observe with care; to notice, observe, and related senses.

I recognise the feeling: an action that is continuous in every note. A doing that is always present or lingers under the surface before it kicks in.

Ordinary Notes is a beautiful book, but it’s also a book about terror – racial trauma, how white supremacy infiltrates every aspect of American life.

A book of encounters where each encounter is allowed to reverberate – denied the escape of narrative flow we sit with each moment, paragraphs, single sentences occupy: bounded by space.

Sharpe translates one form into another, each object she encounters hewn into a memorialisation the experience of which often leaves one stranded – the edge of the next page – she pulls us up. Her book becomes a cartography of living, tracing how history continually impinges on the present.

Structures of violence bare down, she tunnels out, deftly swerves into a clearing to catch her breath.

Time folds back, gaping, Charlottesville Virginia 2017, US Capital building 2021, the Bell Hotel, Essex 2025, a continuous action. Glasgow, 20th September 2025 a man has adapted the Union Jack into bat wings “I was never brought up to be a racist person but –”

Barely gaining traction with the wind, Saltire crumpled across her shoulder ’Clean out the illegals.’

Dawn: verb is action, the action that is ever present. Beautiful in her pleated skirt pinched in at the waist; she holds herself against the flow, cradling her book; perhaps it’s the knuckles wound slightly too tight round the edges that gives us a clue; a delicate frame with a dimple in her chin, Elizabeth Eckford – braced. Behind her, the same grimace which met her, now outside the Bell Hotel. Sara Ahmed plays it differently in The Cultural Politics of Emotion but it’s the same action, economies of affect like the plasma from the screen – it’s all connected.

Seeing for Ourselves And Even Stranger Possibilities by Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan starts with the simple desire to extract herself from the gazes that constrain her; she interrogates her impetus to write – her excessive archiving, untangling the systematic purging of the atrocities of empire in relation to her own and her Grandparents’ inability to remember the simplest of events. ‘Operation Legacy’ was a policy implemented whilst former colonies became independent; documents that were deemed too sensitive for the newly emerging post-colonial states were burned, redacted, some sunk in the middle of the ocean – her archiving becomes a ‘fortress in the face of erased erasure.’

In her choice of examples of how imperial ideologies invade not only land, but mind and body, Manzoor-Khan highlights a moment when an Indigenous woman from Greenland recalls her thirteen year-old self being taken out of class, told to remove her underpants by a doctor, who then ‘forced an IUD contraceptive device into her child sized uterus’.

Memory, or the lack of it, underpins most of the book, it is Manzoor-Khan’s material which she wields sometimes as a weapon and sometimes as a balm; recounting a trip she took to her Grandmother’s township in Pakistan; her Nani’s footsteps activate a map of familial relations; to counter Google Maps’ ignorance of the locality, Manzoor-Khan renames houses and streets ‘the house of the cousin with three ducks […] Uncle dispute land.’

It is Manzoor-Khan’s sensorium that weaves all these disparate elements together; a Chocolate Flake Soft Scoop ice cream melts too quickly while she reinterprets Plato’s Cave, and al-Ghazali’s commentary before forming her own interpretation.

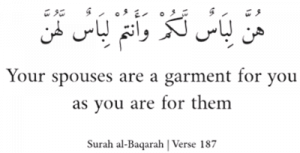

Intimate portraits and interactions with her loved one’s counter outside forces that pierce the everyday domestic sphere, in the chapter ‘Grief is a type of Ghaib/love is a type of sight’ Manzoor-Khan quotes an ayah from the Quran where spouses are referred to as garments for each other.

ل ب س (laam Ba Seen) – ‘root letters linking to concepts of clothing’ (libaas), enveloping, surrounding, and accompanying: a constant between our inner vulnerability and the outer world of appearances; in many ways her book is also a garment, informing a journey to understanding both the complexity of Islamic thought and how Islamophobia is choking not only those within, but also those seeking refuge on, our shores.

Remnants of Partition: 21 Objects from a Continent Divided, Aanchal Malhotra (Hurst, 2019)

Seeing for Ourselves: And Even Stranger Possibilities, Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan (Hajar Press, 2023)

Ordinary Notes, Christina Sharpe (Daunt Books, 2023)

Please note the views published in What I am Reading Now… are personal reflections of the contributors.

These may not necessarily represent the views of the University of Dundee.

———

Previous Issue: Viola Yeşiltaç, December 2025

Next Issue: Ibrahim Nehme, February 2026