What I am Reading Now…

Chrystel Oloukoï

October 2024

‘I plead drunkenness

I am intoxicated

With anger’

(Dung of Chicken)

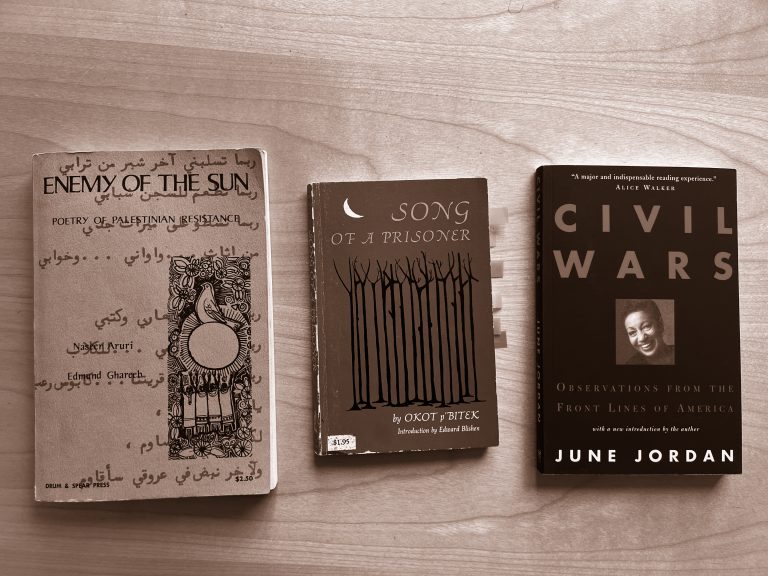

Anger, as a structure of feeling, aptly portrays this season of grief, in the midst of unrelenting genocidal violence unleashed in Congo, Palestine, Sudan, and many other places. Ugandan poet Okot p’Bitek pleads with insurrectionary panache in Song of a Prisoner (1971), a satirical lament on postcolonial disenchantments, and poetic analog to Ivorian novelist Ahmadou Kourouma’s Suns of Independence (1968). The plea, as a repeated structure, sutures fragmented poems into a singular song: ‘I plead guilty,’ ‘I plead drunkenness,’ ‘I plead hunger,’ ‘I plead smallness,’ ‘I plead fear,’ ‘I plead hopelessness,’ ‘I plead helplessness,’ ‘I plead insanity . . .’ I return to Song of a Prisoner often, as a touchstone, and often still, I pause at the dedication:

‘for

lumumba mondale kimathi mboya tshombe balewa . . .

none of whom

will ever read it

and for the

bruised others . . .’

And yet, this thunderous and indocile ensemble, is full of visions of freedom, utopias in supine position and radical openness to a world still worth fighting for. I, too, want to ‘swim in the naked air / Of the dying night.’

With the usual reactionary politics of US electoral season pressing upon us — non-citizens of an empire with worldwide reach — I immersed myself, with even more urgency, within a Black radical tradition unbounded from the state and aspirations to assimilate into violent regimes. I settled on two books of June Jordan’s political essays, Civil Wars (1964-1980) and On Call (1979-1985). Subtitled ‘Observations from the Front Lines of America,’ Civil Wars, as well as On Call, fit squarely within a radical Black feminism that understood the distinction between foreign policy and domestic matters as a white supremacist ruse. As Toni Cade Bambara in Vietnam, Demita Frazier, organising antiwar protest from her Chicago high school, or the Combahee River Collective’s proud assertion of being ‘third world women,’ June Jordan knew that either in Harlem or Nicaragua, she was facing ‘the unreal scene of a full-scale war with no one but enemies in view.’ (Civil Wars, 18).

These multidirectional paths of solidarity are also evident in the traces of smuggled Palestinian resistance poetry within the walls of the California San Quentin maximum security prison. Enemy of the Sun a poem mistakenly attributed to George Jackson, was in fact the work of his brother in arms from faraway lands, the multiply incarcerated poet Samih Al-Qasim. The poem is the title piece of a precious anthology of radical Palestinian poetry edited by Naseer Aruri & Edmund Ghareeb, Enemy of the Sun (1970). Published by the DC-based Black revolutionary press Drum and Spear, it was gifted to me by a friend and abolitionist comrade, Abdulrahman, met in the Paris Sudanese refugee camps, a little over a decade ago. This is a collection of ‘miraculous weapons’ (Cesaire), of ‘poems that kill (…) poems that wrestle cops into alleys’ (Amiri Baraka). Nizar Qabbani narrates his metamorphosis ‘From a poet of love and longing / To one who writes with a knife’ (‘Reflections on the Tragedy — I Mourn (1967)’), joining a fellowship of poets that ‘sharpen pencils on [their] ribs’ and ‘explode mines in words’ (‘To the Poets of the Occupied Territories’). What strikes me the most is the tenderness of the address, in poetic offerings of solidarity in struggle. ‘My brothers’ says Salem Jubran in ‘American Indians.’ Tawfiq Zayyad opens his poem ‘Cuba’ with ‘My friends’ sending to kindred lands of resistance, ‘greetings / Scented kisses — delicious bozes of sweets (…) / And songs of magic.’ Al-Qassem in ‘Patrice Lumumba’ calls the Congolese fallen revolutionary, ‘the poet of freedom,’ while Hadia Abdul-Hadi in ‘From Vietnam,’ asserts family ties between Palestine and Vietnam, as frontlines of US imperialism. In all these places, Mahmoud Darwish reminds us, ‘each dawn has a date with revolution.

Chrystel Oloukoï is an artist, film critic and curator, broadly interested in experimental cinema, queer cinema and Black continental and diasporic cinema. They hold a PhD in African and African American Studies from Harvard University and work at the University of Washington as an assistant professor of Geography. Their work engages imaginations of the night in Lagos, as well as the afterlives of colonial technologies of temporal discipline.

Reading

Song of a Prisoner, Okot p’Bitek (Third Press, 1971)

Civil Wars, June Jordan (Touchstone, 1995)

On Call, June Jordan (South End Press, 1985)

Enemy of the Sun, eds. Naseer Aruri and Edmund Ghareeb (1970, Drum and Spear Press)

Please note the views published in What I am Reading Now… are personal reflections of the contributors.

These may not necessarily represent the views of the University of Dundee.

Readers who wish to make a donation to support Medical Aid for Palestinians can do so here.

———