Dr Nandan Mukherjee, Binks Institute for Sustainability and the UNESCO Centre for Water Law, Policy and Science. School of Humanities, Social Sciences and Law. nmukherjee001@dundee.ac.uk

Returning from COP30 in Belém, one is immediately struck by the extent to which water shaped the agenda. From the first day, “Water” appeared prominently among the Presidency’s thematic priorities, placed alongside adaptation, cities, infrastructure and waste. For those of us working in water governance, this early visibility was significant. It signalled an emerging understanding within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that climate change is experienced, mediated and ultimately measured through water: through droughts and floods, shifting rainfall patterns, declining water quality, and the growing uncertainty of hydrological systems.

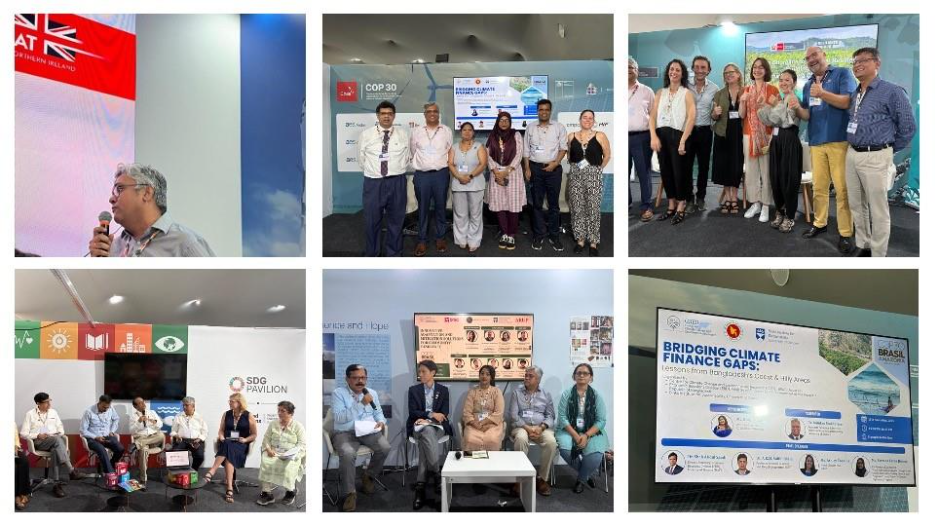

I experienced this contradiction firsthand. As part of the Loss and Damage negotiation team, I worked with countries fighting for recognition of the losses and damages they endure and for access to resources that remain frustratingly out of reach. Outside the negotiation rooms, I represented the University of Dundee’s work on climate-resilient homes, climate justice, food systems, health, and locally led resilience solutions at several side events. Across these diverse spaces, one truth kept resurfacing: whether we are discussing adaptation, food security, health systems or just transitions, we are ultimately talking about water.

Water appeared more prominently at COP30 than ever before. From day one, water was listed as a core thematic focus, signaling that the presidency recognised the hydrological dimensions of climate change. The Water for Climate Pavilion, now involving more than seventy global organisations, emerged as one of the conference’s most active convening spaces. The first meeting of the Baku Dialogue on Water under the Brazilian presidency underscored the growing recognition that water governance underpins both adaptation and mitigation. In negotiations, too, water gained new institutional footholds: for the first time, the Global Goal on Adaptation included a set of water security indicators that offered countries a clearer, though still imperfect, way to track resilience. And one of the few concrete investment decisions was explicitly water-related, the announcement of a Latin America & Caribbean Water Investment Programme mobilising US$20 billion by 2030 to improve drinking-water supply, modernise irrigation, and strengthen flood and drought resilience.

These signals matter. They point to a growing recognition that the climate crisis is fundamentally a water crisis. Yet they also reveal the enduring gap between visibility and centrality. COP30 made progress on water, but it did not become the “Water COP” many hoped for.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the Mutirão Package’s first major outcome: adaptation and climate finance. For decades, adaptation has been acknowledged rhetorically but underfunded in practice. COP30 marked a meaningful shift, with countries agreeing to triple global adaptation finance by 2035 and launching the two-year process to operationalise the COP29 commitment of US$1.3 trillion per year for developing countries. This could become the largest coordinated investment in climate resilience ever attempted. The adoption of 59 global adaptation indicators was a moment of genuine progress: a move away from performative diplomacy towards measurable outcomes that can be scrutinised. However, we must also be honest. Developing countries are hopeful, but not naïve. The world never fully delivered the original 100-billion-dollar promise from more than a decade ago. So when we now speak of 1.3 trillion, a fair question hangs in the air: Will it materialise? And if it does, will countries most at risk actually be able to access it without drowning in bureaucracy?

And when viewed through a water governance lens, these advances remain partial. The water indicators, though welcome, remain narrowly framed around infrastructure and service delivery. They still fail to capture the systemic relationships among water, ecosystems, agriculture, forests, urban development, energy systems, and public health. Without expanding these indicators into integrated assessments, countries risk improving pipes and pumps while the bigger hydrological risks remain untouched.

The Mutirão Package’s second pillar, just and inclusive transitions, demonstrated a similar pattern. COP30 agreed on a new Just Transition Mechanism that moves beyond the technological optimism of earlier COPs to centre people: workers, women, youth, Indigenous peoples and communities on the frontlines. It acknowledges that a transition that forgets people is not a transition but a disruption. Yet water-intensive industries, water-dependent livelihoods, and communities facing acute water insecurity were not explicitly included. Given the centrality of water to energy systems, agriculture, and industrial processes, this omission reveals how water is treated as a sector rather than as the system that holds these transitions together.

The debates on fossil fuels and nature brought these tensions into sharper focus. There was unprecedented mobilisation from vulnerable nations, youth, and Indigenous movements calling for a binding phase-out of fossil fuels. That did not make it into the final text, which instead committed countries to accelerating efforts to transition away from fossil fuels and produce voluntary roadmaps. These may guide future accountability, but they do not yet constitute a structural shift. And despite the close links between fossil extraction, ecosystem degradation and water risk, the hydrological impacts of fossil dependence again received little formal attention.

The most ambitious achievement at COP30 was the commitment to implementation. Three decades of declarations are enough: it is time to deliver. COP30 reinforced the UNFCCC’s delivery and accountability mechanisms, vowing to speed up finance, technology, and support pipelines. Implementation now defines the Mutirão Package.

Yet here, too, water was both everywhere and nowhere. Implementation will ultimately succeed or fail on the strength of water systems: flood protection, urban drainage, river basin governance, aquifer management, drinking-water quality, sanitation, irrigation efficiency, and the legal and institutional frameworks that allocate water fairly. But water was not positioned as the organising principle for implementation. It was acknowledged, referenced, symbolised, but still not centred.

This is the paradox of COP30. Belém elevated water more than any COP before it. New dialogues were launched, indicators were adopted, regional finance was committed to, and UNEP’s role in aligning water across climate, biodiversity, and desertification processes was strengthened. But these are steps toward coherence, not the foundation of a global water regime. The COP did not deliver a binding water security pact, nor did it create a global mechanism for water-related loss and damage. The most vulnerable communities, those living with drought, floods, saline intrusion, and collapsing water quality, still lack a coordinated international framework that recognises water security as the cornerstone of climate resilience.

COP30 stands out for its collective determination, its emphasis on adaptation, and its movement from promises to tangible delivery. Yet this progress is incomplete. Until the UNFCCC places water at the very core of climate governance, global resilience building will remain fundamentally flawed.

The Mutirão COP moved us closer, but much remains to be done. For those of us in water law, policy, and science, now is the time to act: we must transform this new visibility into effective governance, financing, and accountability systems. Without decisive action to place water at the heart of climate strategies, there will be no meaningful climate justice, no real adaptation, and no true implementation.