PRIMARY CILIARY DYSKINESIA

Beyond bronchiectasis, EMBARC also conducts research into known causes of bronchiectasis – an example of which being Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD).

Beyond bronchiectasis, EMBARC also conducts research into known causes of bronchiectasis – an example of which being Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD).

EMBARC analyses clinical data from those with PCD who have been recruited into the EMBARC registry and clinical/biological sample data from those enrolled into the EMBARC-BRIDGE study to better understand the epidemiology, biology and clinical features associated with PCD.

EMBARC is also carrying out a large scale genetic study called GECCO to identify undiagnosed cases of PCD among those enrolled in the EMBARC-BRIDGE study.

What is Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia?

PCD is a rare, genetic condition affecting approximately 1 in 7500 of the population. It is caused by mutations in 1 of >50 genes involved in the structural or functional development of cilia – tiny hair-like structures that are found in large numbers on the surface of certain cells.

Motile cilia (i.e., those that move) are found on the cells lining the lung, and beat in a co-ordinated, wave-like fashion to clear mucus, bacteria and debris trapped in such mucus from the airways – acting as a first line of defence against infection.

Cilia from a healthy individual

The cilia beat from left to right in a coordinated fashion.

In PCD, the cilia in the airway are abnormal – either in structure, number or in their ability to beat efficiently – and therefore patients with PCD are unable to effectively clear mucus from their airway and have an increased susceptibility to infection.

Cilia from an individual with PCD.

This example shows the cilia beating in a short, circular fashion which is inefficient for the clearance of mucus from the airway. This is just one of the ways in which cilia can appear abnormal in those with PCD.

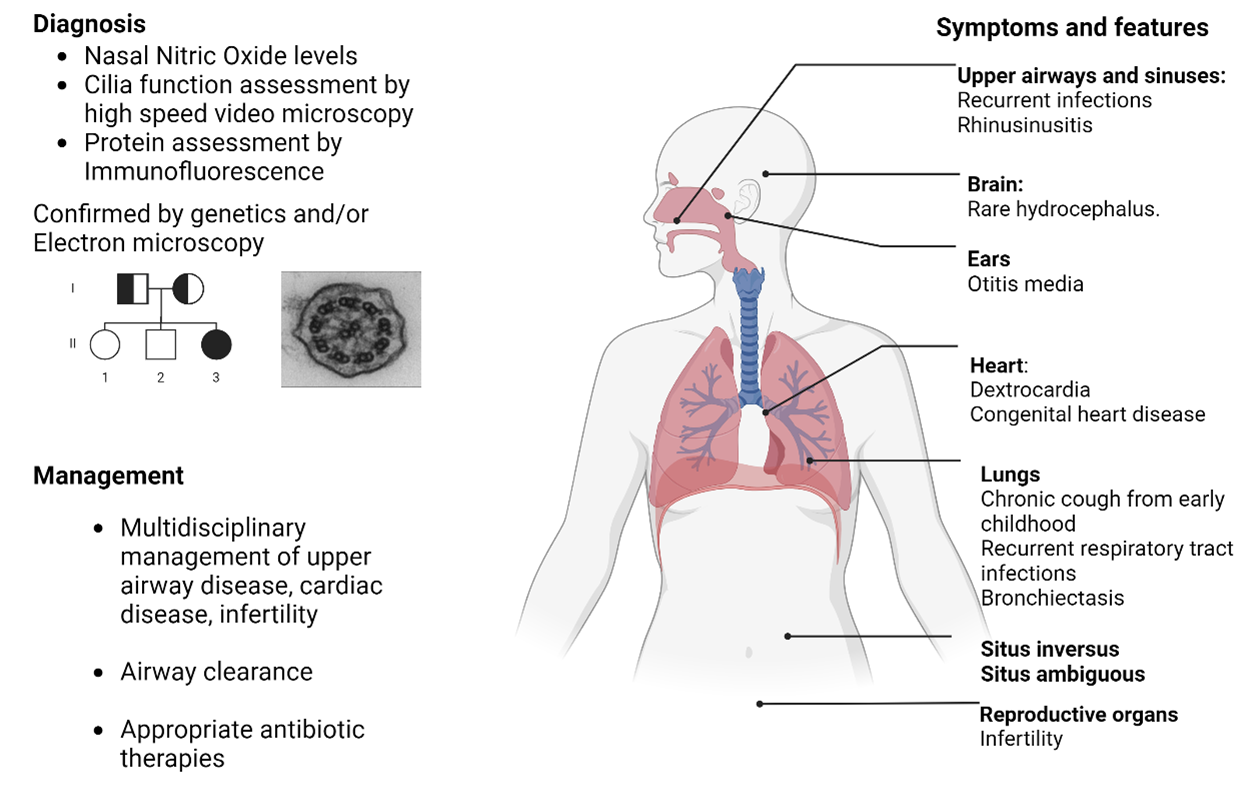

PCD Symptoms, Diagnosis & Management

PCD often presents itself in childhood as neonatal respiratory distress and frequent respiratory infections during childhood, and the majority of patients with PCD go on to develop bronchiectasis in later life.

Cilia are present in other organs as well as the lungs and people with PCD can often present with other clinical features such as situs inversus (reversal of the organs), upper airway symptoms, or infertility.

For a diagnosis of PCD, a combination of functional and genetic tests are used. These can include taking a sample from a patients nose to look at how the cilia function, if they beat efficiently, or their structure under the microscope appears normal. A simpler test for PCD involves measuring the patient’s nasal nitric oxide, but this test cannot confirm PCD on it’s own. A diagnosis of PCD is confirmed by identification of a mutation in one (or more) of the 50 genes known to influence cilia.

The management of PCD is similar to that of other causes of bronchiectasis, with an emphasis on improving airway clearance. Additional multidisciplinary care can be required to address symptoms of other organs as well as genetic counselling where appropriate.

Further Resources on PCD

To learn more about PCD, we encourage you to visit the following resources:

For patients:

Home – PCD Support UK, Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

Clinicians and industry:

For respiratory professionals (clinicians, scientists etc):