Over the past year, photographer and DJCAD alumna Catherine McIntyre has been creating stunning images of the specimens in the D’Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum, which have now been brought together in an online and print-on-demand publication, available to view at www.blurb.co.uk/b/12575243-the-d-arcy-thompson-zoology-museum. Here, she talks about the process and shares some of the images.

Natural history museums are celebrations of life, and also full of death. Their inhabitants are symbols and representatives of whole species. Naturally less than they were when alive, they are still nakedly present, preserved fragments of reality, in which we search for clues to their former selves. Beautiful and fascinating, they are also reminders of mortality – that of all of nature, and of ourselves.

Many of the creatures in the cases no longer exist in any other form. As the early European collections were made, cataloguing, organising and classifying rationalised the natural world. Curiosity drove local collection and expeditions, which filled firstly private cabinets and then the new museums with the wonders of the world.

In a time of change and accelerating extinctions, the purpose of a collection has pivoted. These dead individuals might, we hope, help us to prevent the extinction of their kind. We look for ways in which collections could instruct in potential means of preserving the living.

Modern natural history museums are vital resources to so many aspects of endeavour. Ecologists, environmentalists, zoologists and botanists depend upon them, of course, as do artists, writers, philosophers – people of all creative stripes. These places are fascinating, perplexing, emotive, profound, and inspiring, and essential to us all.

1 Osteology

The collection is particularly rich in osteological specimens. The sculptural qualities of skulls naturally makes them wonderful subjects for photography, and D’Arcy’s collection includes species both native and exotic. There are also many articulated skeletons and individual bones to study.

Left to right: Skeleton of gorilla, skull of lion, skeleton of crab-eating macaque

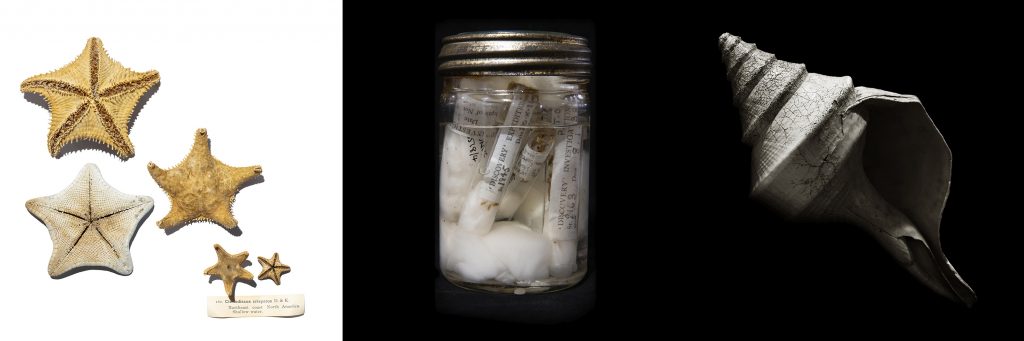

2 Marine life

As Dundee was an important whaling port, sea captains would come back from their expeditions with magnificent specimens for D’Arcy. The collection also benefitted from scientific expeditions such as those undertaken by the Challenger and the Discovery. The collection still rewards research today.

Left to right: Dried sea stars, planktonic crustacea, Australian trumpet shell

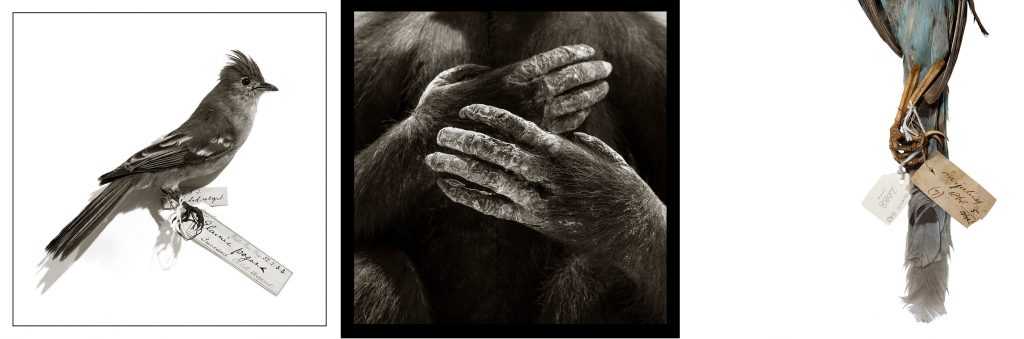

3 Taxidermy

Taxidermy enables the preservation of mammals and birds, in particular, in their most life-like state. Feathers and fur retain their colour and textures remarkably well over centuries, and the addition of glass eyes gives these relics an often uncanny realism.

Left to right: Yellow-bellied elaenia, juvenile chimpanzee, tail of common green magpie

4 Spirit collection

Many specimens, particularly marine ones, are unsuitable for preparation by taxidermy or drying, and are kept in alcohol to preserve them better. Visually, the layers of animal, liquid, glass, condensation and labels make for fascinating distortions and reflections.

Left to right: Chamaeleon, seven-eleven crabs, turtle

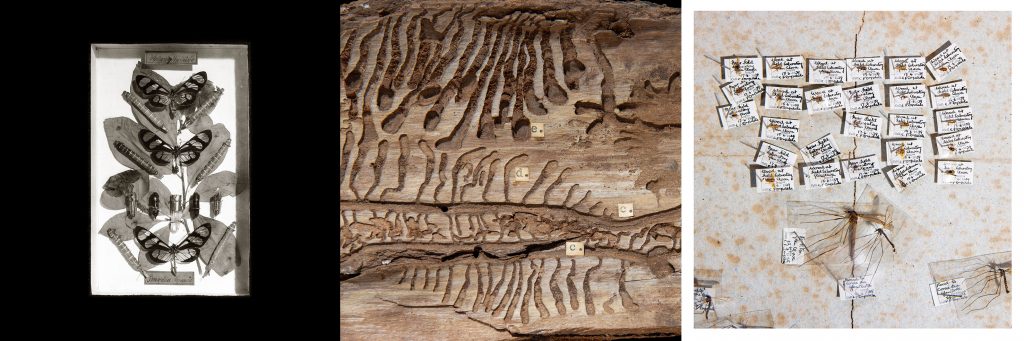

5 Insects

The collection holds the meticulous work of generations of entomologists, in the form of microscope slides, pinned and labelled insects, and boxed sequences of life cycles.

Left to right: Life cycle of themisto amberwing butterfly, excavations of six-toothed bark beetle, insect specimens collected from Glen Clova Field Laboratory

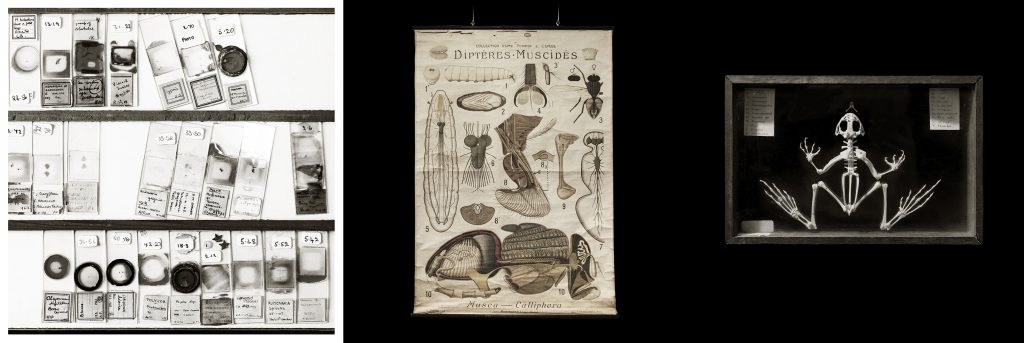

6 Teaching aids

A University natural history collection is special in being specifically designed to educate and explain. Its holdings are a valuable resource not only for students but also for researchers and every scientific and artistic creative, now and in the future. Its importance will only grow.

Left to right: Trays of microscope slides, wall chart of blow fly by Rémy Perrier et Cépède, Paris, skeleton of common frog prepared by Edward Gerrard & Sons, London

[flyntTheContent id=”0″]